SOMR, now in its 12th year, is continuing the work to protect the Macleay. The size of the catchment, the many tributaries, the extractive industries, agriculture and potential pollution of the coastal floodplain give us many and varied points of concern.

Recent issues occupying us include gravel extraction from the riverbed, increasing water use at the top of the catchment and the proposed Oven Mountain Pumped Hydro Scheme.

Overall, the health of the river is at risk.

One of the most important projects SOMR has been involved in is the long term water sampling and quality analysis with the results presented to the interested public at a Community Forum in Kempsey on 8 August.

Over seven years, from 2016 to 2023, SOMR members and citizen scientists Arthur Bain and Nise Grant collaborated with Professor Scott Johnston of Southern Cross University (SCU), collecting water samples for testing.

The samples were taken approximately weekly at Bellbrook Bridge and daily during the post-fire flood event in 2020. The samples were primarily analysed for Arsenic (As) and Antimony (Sb). Professor Johnston identified both as “toxic and carcinogenic metalloids that are common co-contaminants in aquatic environments impacted by mining activities”.

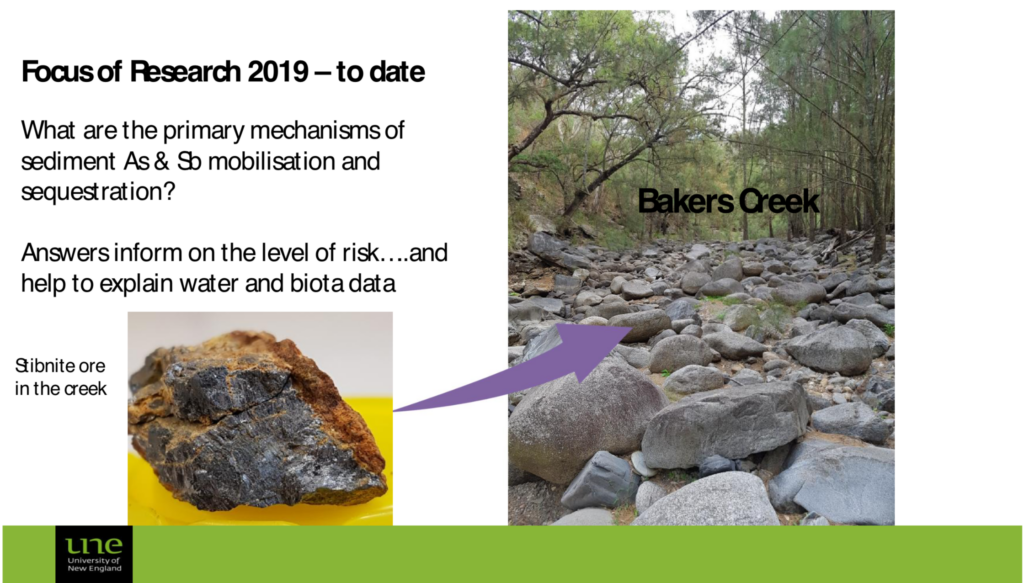

In the Macleay Catchment, the main source of As and Sb contamination are the historic mining tailings in Bakers Creek below Hillgrove. During the 2020 flood which closely followed the fires, many other elements, including potassium, calcium, and nutrients (N/P) became elevated for a short period.

With numerous graphs, Professor Johnston demonstrated the response of these contaminants to changing conditions of the river. The findings reveal that their concentration differs depending on factors such as water temperature, water base flow rate, water level and size of the contaminant particles and ground disturbance.

Go to Professor Johnston’s presentation

In the light of Climate Change with extreme weather events increasing in frequency and intensity, these findings are of concern. In particular the findings that heatwaves and droughts which increase the temperature and reduce the flow of water increases the concentration of contaminants, arsenic in particular.

17% of samples taken in the 7 year period exceeded the WHO drinking water guidelines for safe levels of Antinomy. While the Arsenic concentration did not not exceed the standards, it is said that there are no safe levels for this contaminant.

Go to After the bushfires

Professor Johnston also advised at the Forum that “iron floc” readily takes up arsenic.

Iron floc forms in the base of intermittent creeks where there’s a lot of iron in the soils & geology. Iron oxides with elevated arsenic can be transported downstream during flow events and re-deposited elsewhere in the bed of the river. However, the iron oxides are somewhat unstable and have the potential to release the arsenic that is bound to them if geochemical conditions change. This is a naturally occurring phenomenon, most prevalent where there are a lot of associated metals and minerals present. It is a toxic mix.

Arsenic is in high concentrations, for example below the Mungay Creek antimony mine, which closed in 1972. Should livestock have access to (or humans pump from) the floc area and drink from the water with iron floc, they are likely to ingest the bacteria with the arsenic. Arsenic is an accumulative poison to mammals, which builds up and is very difficult and/or slow to get out of the body. One farmer at the Forum, raising cattle at the mouth of Mungay Creek, reported losing stock to this and advised he would be fencing off his creek frontage.

For many years, scientists from University of New England (UNE) have studied the contamination originating from historic mining, in particular at Bakers Creek. Professor Sue Wilson and her team could not attend the Forum at Kempsey. However, she provided a brief summary of their recent work which was kindly presented by Professor Johnston at the Forum. He has also studied this source of the river contamination.

Go to Brief summary of UNE research

By combining the results of the SCU research with earlier research by UNE allows the conclusion that it will take 600 to 1000 years for the additional Antimony associated with historic mining to be washed out and Bakers Creek to return to natural conditions.

The data derived from these studies provide a unique and excellent baseline for the identification of any impact of future disturbances in the Macleay catchment. Such additional contamination may be caused by further mining or by earthworks necessary for the proposed Oven Mountain Pumped Hydro Scheme. Building two reservoirs as well as the access road and transition lines require major disturbances causing mobilisation of As and Sb and are of great concern for SOMR.

The question is how much more contamination can the river system take before it is too toxic?